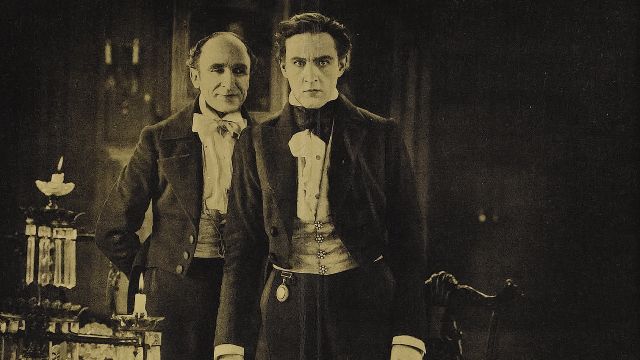

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920)

“The world’s greatest actor in a tremendous story of man at his best and worst!”

Director: John S. Robertson

Cast: John Barrymore, Martha Mansfield, Brandon Hurst

Synopsis: Dr. Henry Jekyll experiments with scientific means of revealing the hidden, dark side of man and releases a murderer from within himself.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s oft-filmed tale of man’s dual nature received yet another airing in 1920 — it had already been filmed at least twice by then — and this time it’s matinee idol John Barrymore trying his luck as the ill-fated doctor. Stevenson’s story has been filmed many times since, thanks largely to its theme of self-destruction, and of the seeds for it which dwell within each of us. The story could just as easily be seen as a metaphor for alcohol or drug abuse, another timeless subject which might explain just why we never seem to lose our fascination with Jekyll and his alter-ego, Mr. Edward Hyde.

Jekyll’s altruistic credentials are established early on in the film as we see him neglecting his long-suffering fiancee Millicent Carewe (Martha Mansfield) in order to attend to the needs of the noble weak and poor at his free surgery. Like Millicent’s father Sir George (Brandon Hurst) it’s difficult to believe anyone can be quiet as goody-goody as Jekyll appears to be, and it’s his mistrust of Jekyll’s saint-like devotion to the crippled poor that sets in motion the chain of events that will ultimately lead to the good doctor’s downfall. Sir George is a bit of an old rascal, if you know what I mean, and has been around the block a few times, and at a dinner party one night he challenges Jekyll to be more adventurous: ‘in devoting yourself to others, aren’t you neglecting the development of your own life?’ he asks, and goes on to claim that ‘a man cannot destroy the savage in him by denying its impulses. The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.’

Now I’m not sure young Millicent would be too thrilled to hear her Dad encouraging her future husband to sow his wild oats while he still can, but that’s pretty much what he does, and Jekyll can’t suppress his intrigue at the old boy’s suggestions. His curiosity is piqued even further when he encounters Gina (Nita Naldi) at a dance hall to which the incorrigible Sir George takes him. Naldi’s dark exotic looks would certainly prove to be a temptation to any man, and she looks genuinely disappointed when Jekyll rejects her advances. But the seeds have undeniably been sown, and he can’t help pondering over how wonderful it would be to be able to separate our two natures so that every evil impulse could be enjoyed while leaving the soul unblemished. He’s right, of course, as we all know. It would be wonderful, and it would be what is known as having our cake and eating it.

Of course, with his scientific curiosity now aroused, Jekyll hides himself away in his laboratory, replete with obligatory test tubes and beakers filled with mysterious bubbling substances from which white steam gently rises, and it’s not long before he’s finally developed a potion he believes will allow his base nature to come to the fore. With a fearless disregard for his own safety similar to that of a small boy breaking into a sweet shop, Jekyll downs his potion and immediately starts pulling a series of increasingly alarming faces. Of course, back in 1920, filmmakers didn’t have even the crude type of special effects that would be around for subsequent versions, so it was pretty much down to Barrymore to try to convey an idea of the pain Jekyll undergoes as his primal nature rises to the fore. Gurning seems to be the path he has taken, although later on he does resort to recklessly throwing himself about like a man standing on a floor through which 5000 volts has been passed. It was probably impressive stuff back in 1920, but it looks more comical than horrific when viewed today.

Anyway, Jekyll emerges from this tortuous transformation looking not a little like Kirk Douglas. He walks with a stoop, his shoulders slumped, his knees bent, and for some reason his fingers grow by a good few inches. Why our baser nature should have longer fingers than our civilised one is a mystery that’s never explained, but a part of me — probably the juvenile part — can’t help wondering whether it’s a sly suggestion that Jekyll is transformed in intimate ways which social and cinematic taboos prevent the filmmakers from showing without resorting to metaphor. Anyway, one thing’s for sure, that Gina from the dance hall is going to find out in double quick time because it’s to her that Jekyll’s inner beast — whom he christens Edward Hyde — immediately heads.

Hyde sets Gina up in a flat so that he can control her life completely, and pretty much spends the next few — who knows? Weeks? Months? — presumably raping and beating her whenever he feels like it, and it’s only when Millicent starts growing concerned about Jekyll’s protracted absence that things eventually come to a head. By this time, however, Jekyll’s been taking the transformative potion so frequently that his bestial nature can now come to the surface at will…

Although lacking access to the quality of special effects enjoyed by later filmmakers, the now-forgotten director John S. Robertson still managed to produce a fast-moving piece of work that never feels rushed or perfunctory. While its narrative perhaps lacks the sophistication of Rouben Mamoulien and Victor Fleming’s versions, it retains all the story’s key incidents and themes. Only Hyde’s relationship with the wretched Gina feels under-developed. This is perhaps a clue to the pressure Robertson was under to play up the more sensationalistic aspects of the tale — such as the giant spider that threatens to absorb Jekyll as he sleeps in a simple but effective nightmare sequence — at the expense of the more introspective emotional issues arising from Jekyll’s transformation. The age of the 1920 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde coupled with the fact that it’s a silent movie precludes it from reaching the wider audience it deserves, but given that it’s a movie that is now in the public domain — and can therefore be freely found on the internet — there’s really no excuse for not giving it an hour-and-a-half of your time

(Reviewed 29th June 2012)

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ho8-vK0L1_8