Psycho (1960)

“The screen’s master of suspense moves his camera into the icy blackness of the unexplained!”

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Cast: Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, Vera Miles

Synopsis: A Phoenix secretary steals $40,000 from her employer’s client, goes on the run and checks into a remote motel run by a young man under the domination of his mother.

Watch this and other movies on Sky Cinema

Watching Psycho today, one can only imagine (and envy) the impression Hitchcock’s classic must have made on its first audiences, seeing it with no knowledge of the unexpected turns in the plot when it was first released in 1960. Today, Psycho is so famous that everyone is familiar with its twists, and although it is still a truly fantastic piece of moviemaking, that foreknowledge of what is to come can’t help but blunt its impact, even though one can still enjoy the style with which it is achieved. Perhaps Citizen Kane is the only other movie that loses little when the twist is known prior to viewing. Some – a very few – movies are so good, it seems, that the famous twists aren’t really the most important thing about them.

Psycho’s twists were unique not because of their shock value, but because of the way in which they wrong-footed the audience. For the first thirty minutes or so we follow the story of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), a dissatisfied secretary whose romance with storekeeper Sam Loomis (John Gavin) is largely confined to illicit liaisons in hotel rooms because of his acrimonious divorce settlement which means he can’t afford to marry her. When the opportunity arises to steal away with $40,000 belonging to one of the sleazy clients of her real estate boss, Marion impulsively grabs it, and sets off for Phoenix to start a new life with her man.

On the road, Hitchcock gives notice of the kind of tricks he’s going to play with audience expectations when Marion is awoken from a nap in her car by a traffic cop. The cop is suspicious of her answers to his questions but allows her to go on her way and, already beginning to feel pangs of guilt, Marion drives immediately to a car dealership to buy a new car. As she talks with the salesman, the cop pulls up across the street and watches Marion. We expect this strand of the story to take us somewhere, but Hitchcock quietly lets it go. Once Marion pulls away from the dealership in her new car the cop is never seen or referred to again.

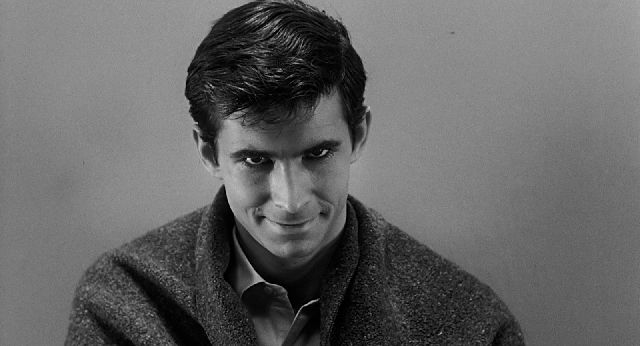

In the middle of a rainstorm, Marion gets lost and makes the fateful decision to pull in at the deserted Bates Motel. Here, she’s welcomed by the boyish Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), and Hitchcock proceeds to set us up for arguably the movie’s biggest twist. After a friendly conversation in which it becomes clear that Norman is living under the thumb of his sick but domineering mother (’A boy’s best friend is his mother,’ he unconvincingly declares with a nervous smile) and Marion reveals her intention to return home, she becomes the victim of a crazed killer.

The shower scene in which Marion is murdered is justly famous, not only because of it’s shock value – audiences in 1960 weren’t used to seeing a lead character killed off before the movie was even half over – but in the way Hitchcock filmed it so that audiences were fooled into believing the violence they witnessed was more graphic than it really was. His use of nearly 80 cuts for the deceptively brief sequence and Bernard Herrmann’s slashing score combined to create a moment of movie history that retains its power more than half-a-century after it was originally screened.

Following this virtuoso moment, Hitchcock demonstrates how skilled he was at manipulating his audience by essentially having us root for the bad guy. After he has cleared up all traces of the murder, Norman pushes Marion’s car – with her body and the $40,000 in the trunk – into a swamp. The car’s descent into the swamp pauses for one tense moment, and we hold our collective breath with Norman before it finally disappears into the swamp. Not only has Hitchcock killed off our heroine, he’s tricked us into colluding with the killer.

In the Robert Bloch novel on which Psycho is based, Norman Bates is an older man, overweight and a bit of a slob, and it was a masterstroke on the part of screenwriter Joseph Stefano to transform him into a personable young man. Anthony Perkins gave a performance that would ensure – much to his chagrin – that his name would forever be associated with the character. Only in the final scenes does he look like a psychotic killer – but in times of stress the mask of normality slips a notch to reveal a nervous twitchiness that paradoxically serves to humanise him. Perkins captures this vulnerability perfectly, sometimes simply by swallowing hard or by tapping a finger at the bottom of the screen, and he creates an intriguingly textured character which goes some way to explaining why he still remains in our collective consciousness.

Few movies are perfect, but Psycho would be were it not for the lengthy, overblown explanatory speech delivered by a psychiatrist (Simon Oakland) following Norman’s capture. Perhaps audiences weren’t quite as sophisticated as they are today, but it’s doubtful that even back then they needed to be spoon-fed so much superfluous information. It’s a minor gripe, but one that, because the sequence occurs at the end of the movie, tends to remain in the memory…

(Reviewed 2nd July 2012)

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ps8H3rg5GfM