The Outlaw and His Wife (1918)

Director: Victor Sjöström

Cast: Victor Sjöström, Edith Erastoff, John Ekman

Synopsis: Committing a petty crime forces a Swedish farmer and his wife into hiding in Iceland.

With The Outlaw and His Wife, Victor Sjostrom expands on the theme of the links binding man and nature which he originally explored in the previous year’s Terje Vigen. Set in Iceland, it tells the simple tale of Berg-Ejvind (Victor Sjöström — Phantom Carriage), a man forced to steal in order to feed his starving family, who is imprisoned for 10 years when the theft is traced back to him. He escapes from his makeshift prison and hides out in the mountains, a favourite refuge for those who fall foul of the country’s harsh laws. Eventually, he seeks work at a remote farm run by Halla (Edith Erastoff — Terje Vigen – who would later become Sjöström’s’wife) and the couple fall in love, much to the annoyance of the local alderman, Bjorn, (Nils Aréhn — Phantom Carriage), the brother of Halla’s deceased husband who wishes to marry her in order to increase his wealth.

Berg-Ejvind’s past catches up with him one Sunday morning when a visitor to the village recognises him and informs Bjorn. Halla hides her lover during the subsequent search for him, and so deep is her love for him she willingly abandons her wealth to live the life of a fugitive in the harsh, forbidding Icelandic mountains. Against the odds, the couple find happiness in the unforgiving wilderness, and even raise a daughter, but tragedy strikes when, after seven years, the authorities once again catch up with them.

It’s strange that The Outlaw and His Wife is told mostly from the viewpoint of Berg-Ejvind, when the character of Halla would surely seem to be the person around whom the story should revolve. She, after all, is the one who gives up her entire life to be with this fugitive who has concealed his past from her, and the reason she makes that monumental leap of faith deserves a good deal more investigation than it receives. Later in the movie, when it looks as if she, Berg-Ejvind and their little daughter are about to be captured, Halla is driven to commit an act that is about as shocking as anything you will find in a movie from any era, and yet Sjöström — or perhaps the source material from which he works — seems unconcerned about exploring what would drive her to such an act which, without such explanation, comes across as jarringly unbelievable. Presumably, the fact that she and Berg-Ejvind are still enduring unspeakable hardship together nearly ten years later is supposed to point to the depth of their love for one another, but without an appropriate examination of his response to the act she committed, the film feels only half-complete.

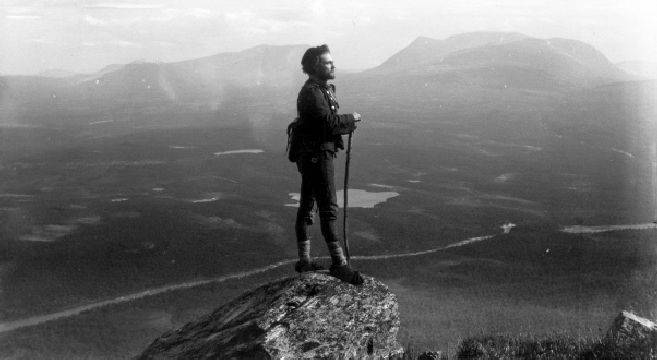

This fatal omission overshadows many of The Outlaw and His Wife’s finer qualities, chief of which is Sjöström and cinematographer Julius Jaenzon’s superb use of the rugged, sprawling Swedish landscape (doubling for Iceland). The terrain really does become a character within the movie, while the seasons reflect the stages of the tragic couple’s relationship. Sjöström makes a robust and vigorous leading man, and while Edith Erastoff might not possess the kind of looks you’d expect would be necessary to entice not one but three men, she does have the ruddy, weather-worn look of a woman who has lived in a harsh environment all her life. After a slow start, The Outlaw and His Wife becomes increasingly absorbing, only to shock the viewer out of the film by one glaring misjudgement which it then virtually ignores during a climax which achieves a measure of poignancy despite feeling rushed and incomplete.

(Reviewed 31st August 2014)

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bEU4wHaP4xo