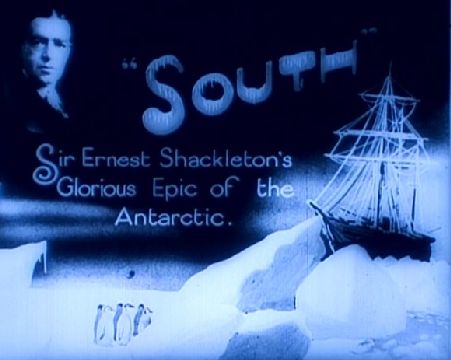

South (1920)

Director: Frank Hurley

Cast: Ernest Shackleton, Frank Worsley, J. Stenhouse

Synopsis: The story of the 1914-1916 Antarctic exploration mission of Sir Ernest Shackleton.

It’s ironic that because it’s a silent movie, South fails to capture how completely silent the landscape in the Antarctic must be. Or more correctly, the occasional sounds that pierce the near-complete silence, such as the creaking of the ice as it slowly moves across the surface of freezing water, or the mournful sweep of the wind. The shot of the ship The Endurance taken at night in the glow of some 20 flashlights is beautiful and haunting enough, but imagine just how much deeper that image would resonate with sound. Nevertheless, South, a record of Ernest Shackleton’s ill-fated expedition to traverse Antarctica, is not only a valuable historical record but also a coldly beautiful account of the brutal, uncaring power of nature at the extremes of the Earth.

It was filmed by Frank Hurley, the captain of The Endeavour. Apparently, agreeing to film parts of the trek was the only way Shackleton could raise enough cash to finance the expedition. Ironically, Hurley ended up shooting not so much a triumphant conquest of the polar ice cap but a nearly three-year test of endurance for the 30-odd men when their ship became trapped in ice which, over a period of months, crushed and sank it with a terrible implacability. The omens were poor from the beginning, with a forced extended stay in Buenos Aires because of the unseasonably bad weather in the Antarctic, but with typical British pluck, the expedition ploughed on regardless. Early shots show the 69 dogs taken on the journey — another commercial decision made to entice audiences into picture houses — and, in fact, the animals play quite a prominent role in the early stages. What the intertitles fail to reveal is that the dogs are nowhere to be seen in the second half of the film because the crew was forced to shoot and eat them when things started getting a bit hairy.

Perhaps this failure on the part of the movie to capture the real hardship endured by both men and beasts is its biggest failing. We know it’s cold down there — and even if we didn’t, the volume of condensed breath we see billowing from one dog’s mouth would be enough to tell us — but Hurley tended to keep the camera at a distance for much of the time, and by doing so inadvertently distanced the audience from the real conditions they encountered and the effect it had on the men.

Once The Endeavour had sunk, the men had no choice but to wait for the ice to melt enough to enable them to sail in lifeboats to a place called Elephant Island, and it’s from this point that the real story of South begins. Unfortunately, necessity meant that Hurley was forced to leave his cine camera behind so that this portion of the tale consists of little more than a few still photographs and some artist’s impressions. Shackleton and two of his men then had to undergo a three day trek to reach help for the injured members of his crew, negotiating a giant glacier on the way, but none of this is captured on film leaving the viewer with a distinct sense of anti-climax. This disappointment is compounded by the fact that the last 20 minutes consists almost entirely of shots of indigenous wildlife — again a commercial decision — which were actually filmed on a return trip by Hurley a year after the expedition’s return for this express purpose.

Of course, you can’t blame Hurley for the way things turned out. Needs must, and all that. But watching South, we get more of a sense of what a great opportunity was ripped away from us than we do of the details of the expedition.

(Reviewed 23rd May 2013)