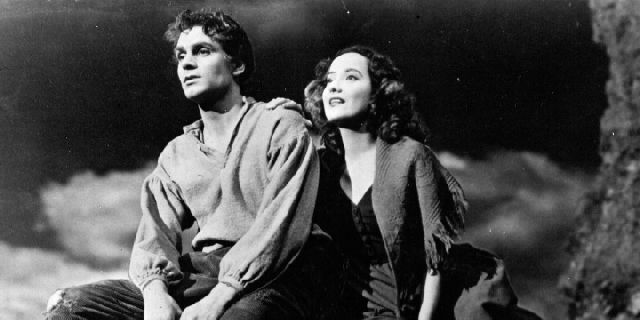

Wuthering Heights (1939)

“I am torn by Desire… tortured by hate!

Wuthering Heights (1939)

Director: William Wyler

Cast: Merle Oberon, Laurence Olivier, David Niven

Synopsis: A servant in the house of Wuthering Heights tells a traveler the unfortunate tale of lovers Cathy and Heathcliff.

Emily Bronte was 29 when Wuthering Heights, her only novel, was published in 1847, and was only one year away from a premature death from tuberculosis. She was a shy woman who led a sheltered life, rarely straying from the family home in Haworth, West Yorkshire, other than to walk in the hills or attend church services. She’d never tasted romance of any kind, a fact which is reflected in the passion — most of it frustrated — and torrid, tragic romanticism of Wuthering Heights. In 1939 it undoubtedly made for compelling viewing thanks to Samuel Goldwyn’s typically lavish treatment, but when viewed today its origins in the expression of the tragic romantic yearnings of a woman of limited experience becomes all too apparent. Bronte may have possessed a unique literary ability, but when given the Hollywood treatment her story is constantly in danger of becoming a Mills and Boon tearjerker. Thankfully, an adult, intelligent script by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, some committed performances from an accomplished cast and assured direction from William Wyler means that Wuthering Heights deserves its’ status as an example of classic Hollywood at its best, despite a few lingering problems.

It’s the middle of the 19th Century, and a businessman named Earnshaw (Cecil Kellaway — The Adventures of Bullwhip Griffin) returns from a trip to Liverpool to his home on the Yorkshire moors with a street urchin he names Heathcliff (Rex Downing — Call Northside 777). Earnshaw’s daughter, Cathy (Sarita Wooten) quickly becomes friends with the quiet, earnest boy, but his son Hindley (Douglas Scott) takes an instant dislike to him. It’s a mutual contempt that lasts to young adulthood when, following Earnshaw’s death, Hindley (now played by Hugh Williams), allows Heathcliff (Laurence Olivier — Rebecca, 49th Parallel) to continue living at Wuthering Heights on the condition that he works as a stable boy. Heathcliff does so only because his love for Cathy (Merle Oberon) is so intense that he can’t countenance a life without her. Cathy feels the same way about him, but their deep bond is concealed from her brother, which means they regularly rendezvous at their ‘castle’, Penistone Crag on the moors.

Cathy’s feelings for Heathcliff become confused when they are caught spying on a ball at the house of their wealthy neighbours, the Lintons. After being injured by one of the Lintons’ hounds, Cathy is invited to recuperate at their home, where she becomes captivated both by their privileged way of life and dashing young Edgar Linton (David Niven — A Matter of Life and Death). Heathcliff is distraught when Edgar eventually proposes marriage to Cathy, especially when he then overhears her exclaiming to Wuthering Heights’ housekeeper, Ellen (Flora Robson) that to marry Heathcliff would be degrading. He doesn’t hang around to hear any more, which is a shame because if he had he would have heard Cathy go on to realise that despite Heathcliff’s lowly status the bond between them is so strong that they are virtually one person. It will be many years before Heathcliff and Cathy meet again, by which time he will have re-invented himself as a man of wealth, and she will have become Edgar Linton’s wife…

The idea of true love frustrated by fickle fate is as old as the hills, but Bronte invested this dated theme with such passion and fury that the story of Heathcliff and Cathy felt new and different. Theirs was the kind of love of which we normal people can only dream, an all-consuming obsession which coloured every aspect of their lives (and deaths). Such magnified emotions run the risk of looking absurd if not handled correctly, and it’s true that Olivier’s lines sometimes take him dangerously close to crossing the line that separates honest expression from tiresome verbosity when describing the depths of his love to Cathy every time they meet. Given that Heathcliff is otherwise a sullen and reserved character, this frank openness would be a little jarring were it not for the contained intensity with which Olivier delivers his lines. While he’s entirely unconvincing as a stable lad, Olivier cuts an imposing figure as a brooding man of wealth, and dominates the film upon Heathcliff’s return from America. Even when he’s not on the screen, his influence controls every scene.

Unfortunately, Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s script can do nothing about actually making Heathcliff or Cathy likeable. He’s taciturn, rude and self-absorbed, while she’s spoiled and wilful and irritatingly fickle. While this might explain her reasons for vacillating between the earthy wild spirit of Heathcliff and Edgar’s cultured status, it also serves to paint her as a spoiled little girl who, as Heathcliff points out, is simply taken with the idea of having a man slavishly devoted to her in the way that he is. Oberon looks gorgeous in the part of Cathy, but struggles to capture the restless, fiery side of her nature, and seems too lightweight an actress to convincingly suggest the tumultuous emotions her character spends half the movie trying to suppress. In fact, she comes off second best to Geraldine Fitzgerald as Isabella, Edgar Linton’s ill-fated sister whom Heathcliff marries as an act of revenge. Fitzgerald demonstrates more honest emotion in the one scene in which, near-defeated and on the edge of despair, she begs Heathcliff to give her a chance to love him, than Oberon manages in the entire picture, and hers must stand as one of the best performances never to win an Oscar (she lost out to Hattie McDaniel in Gone With the Wind for Best Supporting Actress).

Despite all this, Wuthering Heights is still a highly compelling and entertaining movie. It’s a Goldwyn movie — which means it’s a prestige production, but that’s not always a guarantee of quality — and it’s clear that care has been taken to remain respectful to Bronte’s novel while creating a picture that will appeal to a mass audience. The script is near poetic at times, without ever sounding contrived or forced, and William Wyler directs a committed cast with a refreshing clarity of vision.

(Reviewed 2nd September 2014)

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XmuMd4FnnYo