Straight on Till Morning (1972)

Director: Peter Collinson

Cast: Rita Tushingham, Shane Briant, James Bolam

Synopsis: A timid, withdrawn woman meets a man she believes is finally the love of her life, unaware that he is a vicious serial killer.

Mention Hammer Studios and most people will immediately think not of films like Peter Collinson’s Straight on Till morning but of those gothic horrors featuring Christopher Lee and/or Peter Cushing. But Horror also produced movies that had no connection to the classic horror of Dracula and Frankenstein. In the 1970s in particular, as a growing change in public taste was hastened by the release of The Exorcist, Hammer attempted to modernise its output, upping the gore and female nudity in their films in the hope of appealing to a younger audience. It was a tactic that failed, and while it’s not a bad film, Straight on Till Morning is symptomatic of the reasons Hammer’s fortunes declined in the 1970s.

The film opens like some slice-of-life piece of social-realism — all back-street terraced housing and working class décor as we meet Brenda (Rita Tushingham — The Wee Man), a plain Northern lass who fills her time writing children’s fairy tales which are clearly an escape from the dreariness of her own life rather than the product of an ambition to be an author. To the distress of her mother, Brenda is moving down to London to find a man to be a father to her unborn child. Only her pregnancy is another fairy tale, a shocking excuse to leave home without hurting her mother’s feelings. That might not make much sense to you, but we must assume her mother asked any questions she might have had about the baby’s father before the film began and that those questions weren’t too searching, because she asks none on the eve of her daughter’s departure.

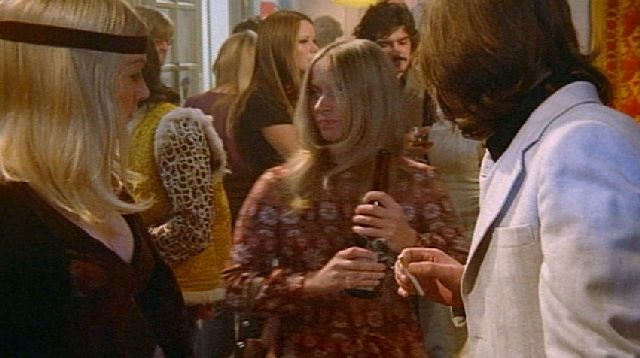

Brenda moves into a squalid room in London and finds work in one of those trendy boutiques that look so dated today. In fact, the whole movie looks incredibly dated, both in terms of the fashions of the day, the acting styles and the filmmaking techniques, but the filmmakers can’t be held to blame for that. No doubt it was cutting edge back in 1972, but it’s just that some eras seem to have aged more badly than others. Anyway, Brenda is befriended by Caroline (Katya Wyeth), a sexy blonde colleague, and soon moves into her flat, much to the annoyance of Jimmy (Tom Bell), the boutique’s owner. But soon after moving in she meets Peter Clive (Shane Briant), a pretty young man with flowing blonde hair and soft white skin and it’s not long before she moves in with him. What Brenda doesn’t realise is that Peter is a serial killer…

Straight on Till Morning, as the title suggests, incorporates references to J M Barrie’s Peter Pan in its storyline, although why exactly is something of a mystery. It does dovetail with the fascination both Brenda and Peter have with children’s fairy tales, and perhaps refers to Peter’s suspended emotional development, which lies at the heart of his compulsion to kill, but otherwise the links are tenuous at best. Brenda and Peter are mirror images of one another: she’s a plain girl who craves love, while women’s apparent infatuation with Peter’s own physical perfection has triggered within him a murderous revulsion towards the concept of perfection. Brenda’s plainness and initially unquestioning acceptance of Peter’s eccentricities make them a near-perfect match, and for a while it looks as if they really have a chance of making it. But all fairy tales are based on a dark premise, and Straight on Till Morning holds true to this fact.

While the relationship between Brenda and Peter is an intriguing one, John Peacock’s screenplay doesn’t quite seem to know what to do with them at times, and the film drags considerably during the second act. Peter Collinson’s sometimes flashy direction is also a distraction, filled with too many gimmicks in a futile attempt to inject some ill-advised artiness into a project that doesn’t really call for any. In fact, as scenes unfold you can almost sense a struggle of wills between Collinson and the studio executives with an eye on box office potential, and it sometimes makes for an uneasy fit. But the movie delivers an unexpectedly strong final act, with its horrors suggested by sound rather than vision. For this at least, Collinson and Peacock deserve credit for trying something different.

(Reviewed 24th March 2014)

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NxBr_OjIK9s